Improving User Experience with Diary Studies

How We Used User Diary Studies to Evaluate and Improve Our Product Before Launch

This article is the transcript of a talk I presented during an online meetup. I explain how we used diary studies to evaluate how users interacted with the product over time, on a large-scale redesign project. This helped us improve the product a lot before final launch. I share my process step by step—from setting up the study to analyzing the results—and shared key takeaways. If you are curious about how diary studies can help improve a product or looking for practical examples of diary studies in action, you are in the right place. Go directly to the video if you prefer to watch the reply.

Vous pouvez lire cet article également en français

Background: Migration of an 18-Year-Old Enterprise Tool

Let me give you some background on the project. I work for an investment bank in Luxembourg. We were redesigning and migrating an 18-year-old enterprise tool used for managing loans across Europe (and beyond). This tool had 400 pages and was used daily by over 2,000 people at the bank. Users rely on it for many tasks. They create loans, tracke their progress, disburse money, monitor repayments, and handle many other activities. The variety of tasks is, quite big.

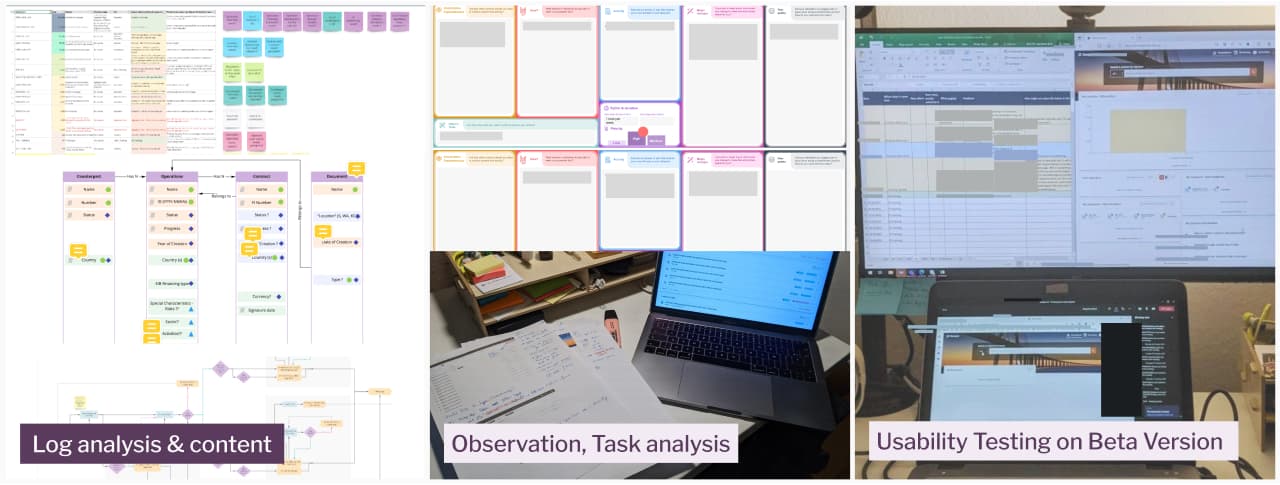

Starting with Quantitative Data

We needed to migrate 400 pages, so we began with quantitative data. We analyzed server logs to determine which pages were most used. This gave us a starting point, helping us identify which pages to prioritize. However, this data didn’t explain why users visited these pages or what content was essential versus unnecessary.

Task Analysis and Discovery Research

Next, we conducted discovery research. We scheduled many interviews to understand tasks, activities, pain points, needs, and frustrations. Since this was an enterprise tool used daily, we focused the interviews on task activities. We asked questions like:

- What are users trying to achieve?

- How do they accomplish it?

- What dependencies and tools do they rely on?

- What are their biggest challenges?

Finally, we asked how they would improve things if they had a magic wand. To structure the search, we used Geoffrey Crofte’s & Julie Muller User Task Canvas – Cards & Interview Guide and created a Miro board.

Observational Usability Testing

Using our research, we built initial pages for the new tool. We worked in agile, which meant we released new pages and features along the year. Once we had enough pages, we conducted observational feedback sessions using a beta version. Users were asked to perform tasks they would typically do with the old tool but using the new one instead. With only an hour per session, we couldn’t capture all the tasks people did on a daily basis.

Sidenote: if you need help with user interview and usability testing, I have many templates to save you time while preparing and running suche sessions in my shop

Check ou the UX Templates Shop

The need of a diary study

Because of the diversity of tasks users carried out with the tool on a daily basis, it was impossible to cover everything during the 1h 1to1 testing sessions. We needed a self-reporting method to collect data on real usage over a period of time. This is when we decided to run some diary studies.

What is a Diary Study?

A diary study is a self-reporting research method that lets us evaluate the experience of a group of users with a product or service over time. Participants report their own actions, experiences, and behaviors over a period of time. They can use text, photos, videos, or voice recordings. The format depends on the research goals and the type of data needed.

Diary studies are often used during the exploratory phase of a project. However, they are equally effective for evaluation, as in our case. This method allowed us to collect real-world usage data over time without needing to observe users constantly—ideal for our complex tool.

Setup and Preparation

To run a successful diary study, preparation is key. Here’s how we approached it:

Building the Research Plan

Like any structured research project, we started with a research plan:

- Define the Research Goal: Determine whether users could rely on the new tool daily without needing to come back to the old one. We also wanted to identify gaps and issues.

- Determine the Scope: Over two years, we conducted the study with four user groups, each accessing the beta at different times.

- Set the Duration: Initially, the study was planned for one month. However, most participants requested extra time, so it often extended to six weeks or more.

Preparing the Diary: What to Capture and How

Deciding What to Capture

You can capture various aspects such as tasks, habits, motivations, difficulties, and feelings. Our focus was on pain points—things that prevented users from completing tasks. Participants logged what went wrong and included screenshots when applicable.

For ethnographic studies, additional context like videos or recordings might be useful to understand the environment and artifacts involved.

Setting Triggers

Triggers determine when participants log entries. They can be:

- Specific intervals: Regular logging, e.g., every three days or every Thursday.

- Event-based: Logging only when specific events occur.

- Prompts or signals: Manual or automated reminders to log entries.

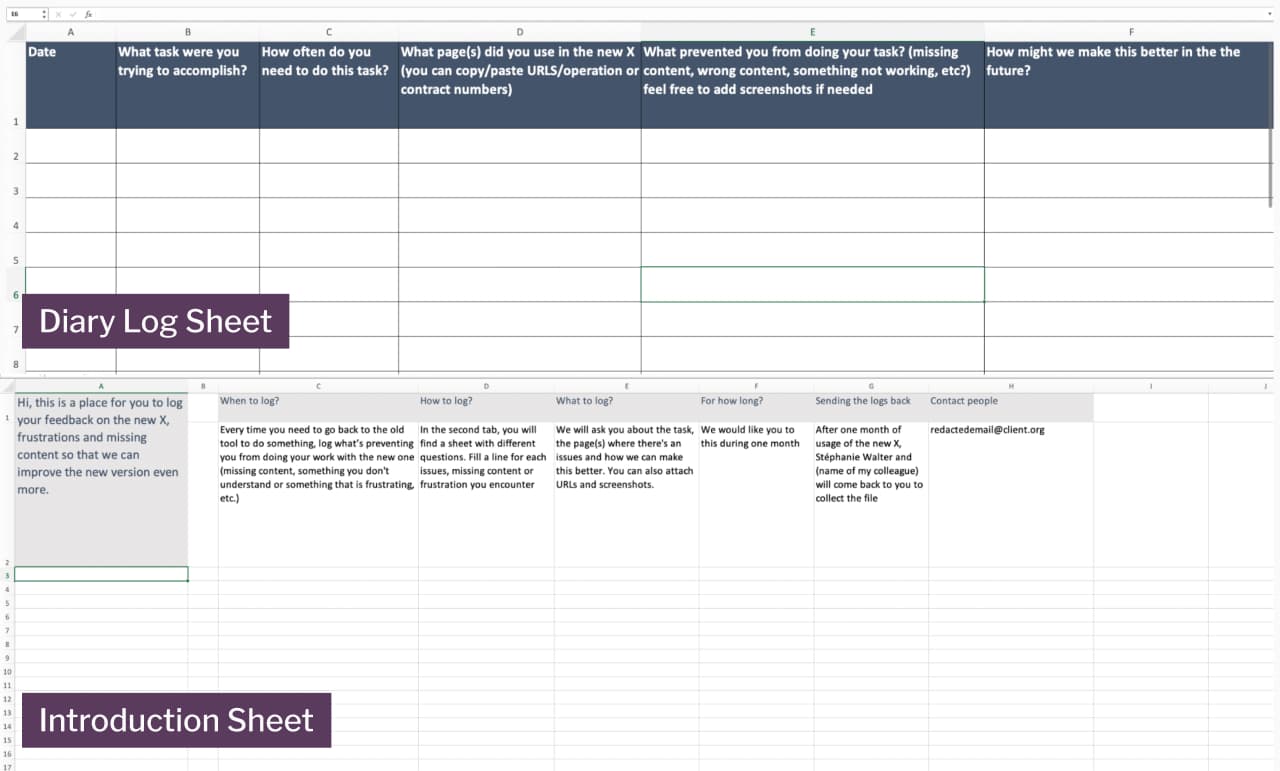

We used the following event-based triggers: “Every time you need to go back to the old tool to do something, log what’s preventing you from doing your work with the new one (missing content, something you don’t understand or something that is frustrating, etc.)”

Deciding Format and Tools

Diary formats can be open (freeform entries), closed (structured questions), or mixed. We opted for a mixed format.

Since our participants worked in a bank, we used Excel. It wasn’t flashy but was familiar and easy to use.

Other options include

- Digital diaries: Word, Google Doc, Powerpoint, etc.

- Dedicated survey tools, as long as they let you submit the same form multiple times).

- Communication tools, like Slack, SMS, perfect for direct prompt.

- Paper diaries: for example, during a study in Luxembourg on habitant’s consumption habits, participants were sent paper diaries. They were asked to log all their household purchases over a two-week period. Yes, on paper. After 2 weeks, they had to send the paper diary back.

For survey tools, the one I use is UX Tweak. They have a survey tool where users have options to submit it multiple times. If you are interested, you can use my UX Tweak affiliate link for 10% discount or the code STEPHANIE10.

Conducting the Study

Pilot the Study

Before launching, we piloted the study with internal team members. This helped us refine the questions and identify any technical issues.

Recruitment

Diary studies require significant commitment, so transparency is essential.

When recruiting, here are few things to be careful about:

- Be transparent about the time commitment for the study from participants

- Offer compensation that reflects the time/effort involved

- This method has more drop-outs than with other methods. Which means: you might need to schedule more participants to compensate for drop-outs.

Kickoff and Follow-Ups

We began with a kickoff session to:

- Explain the study’s goals and duration.

- Teach participants how to log entries.

- Provide contact information for support.

If the study lasts for a long period of time, remember to follow up with participants, especially if you see that the data is not coming in. We sent quick emails regularly to keep participants engaged and make sure they were logging entries.

Collecting the Diaries

If you don’t collect the data live and have a diary people need to send back, here are a couple of things I recommend:

- Send participants a notice, a few days before collecting the diaries back

- Make it easy for them to get it back to you

- Thank participants and explain how to get the compensation.

On my project, a couple of days before the deadline, we sent reminders to inform participants we would be collecting them soon. They would send them back by simply replying to the reminder. We only had 20% of people who never sent anything back, which is honestly not bad.

In the diary study on consumption in Luxembourg, they made it very easy for participants to return their diaries. Each package included a pre-paid, pre-filled envelope. Participants only had to place their completed diaries in the envelope and drop it in a mailbox.

Analysis and Using the Data

For context, remember that the data here is feedback on using the new tool for a whole month. Analyzing diary study data takes some organization. Remember that the more data you collect, the more time it will take to analyze it. I won’t go into the details of how to run a quantitative and qualitative analysis, but I’ll explain how we handled our:

- Merge and clean up duplicates: once we got the diaries, we merged all the entries into one single Excel sheet and removed duplicates.

- Categorize: there’s no magical way to analyze such an amount of data, you need to go through it. With a colleague, we read every entry, and we tagged it by type (like usability issue, bug, or improvement) and gravity (from minor to critical).

- Clean up again: we run a second round to remove the bugs from the list and treat them separately.

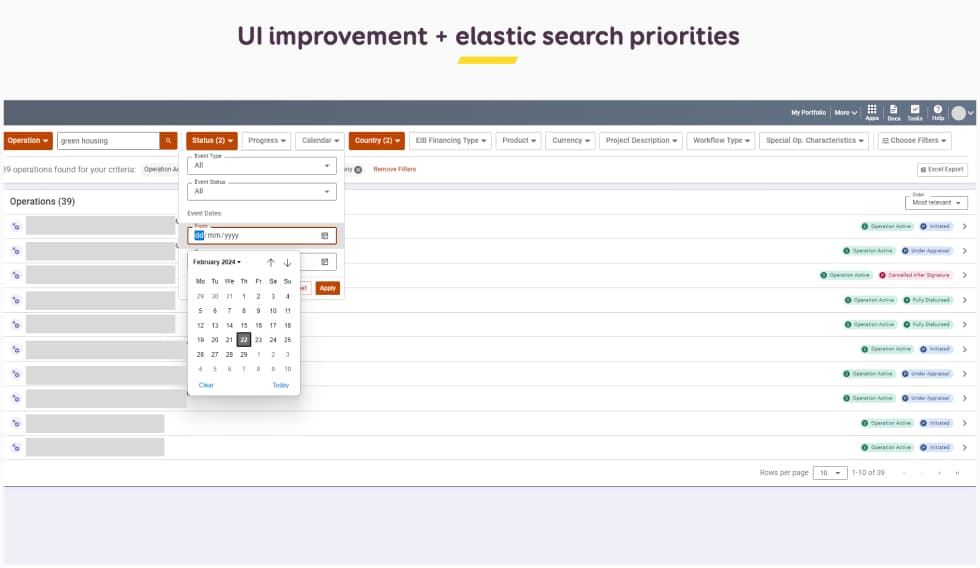

Identifying Themes - Find Themes: we looked for patterns in the data, like recurring issues with search functionality. These themes helped us decide we needed to improve, where we needed to rework the interface or adjust the search engine.

- Take Action: First, we fixed the bugs that were reported in the diaries. For some usability issues, we reached out to participants to get more details (this is discussed further in the follow-up section). Next, we improved the UI to address recurring pain points. We also identified missing content and made it a priority for migration. Finally, we developed training materials to help users adapt to the changes. These resources included FAQs, videos, and training sessions tailored to their needs.

Sidenote on training: when you work in enterprise environments, often users expect training in different forms (FAQ, videos, actual training sessions, etc.). It doesn’t mean you failed as a designer, it means you work in a very complex environment where people need help doing their job with the tool.

Follow-Up

The study doesn’t end when you collect the diaries. Follow-ups are very important. Here’s a couple of follow-ups we did with some or all users:

- We clarified unclear entries by asking participants for more details, in 1 to 1 sessions.

- We explored new topics that came up during the study and confirmed missing content in 1 to 1 follow-up sessions.

- We shared a summary of findings and actions with participants, showing how their feedback shaped the next steps.

The goal is not, of course, not to dump our whole backlog in them. But, I’m working directly within the company, my users are my colleagues, and the whole project was built on trust and transparency.

You can also use follow-ups to ask participants feedback about the diary study itself, especially if you want to run it again later.I

Continuous Improvement of Product

The feedback from the diaries influenced our roadmap, and helped keep on improving the tool before the final public launch. They were a goldmine for continuous improvement. They helped us:

- Collect data in context, for real use cases that we could not capture with usability sessions

- Discover non-migrated content that was still very essential for our users

- Identify specific usability issues on topics that can’t be covered during usability testing sessions

The data collected helped us to greatly improve our search for example. It’s one of the key features of our tool. And users use it for different purposes:

- Search for something specific

- Build a list of items using different criteria

- Find “similar” content to compare to their own

Search is one of the tags / themes that had the most entries in the diary. It’s hard to measure how effective and useful a search engine is during a user test. The results depend on what the user is searching for at that specific moment. We knew we needed to improve those, we just didn’t know how and what people were expecting.

During the diary study, people would perform actual real searches on the beta version on a daily basis. They then logged into details what didn’t work for them.

With all this feedback helped us improve our research:

- We reworked the UI to offer essential filters that were still missing

- We reworked the priorities of our results with the elastic search engine.

- We changed what is expected as results from a full text search, with or without exact matches.

- We reworked the order and filtering of results, etc.

Conclusion: Benefits and Limits of the Method

Benefits

This method lets you collect data and feedback over time which means:

- Collect Data Over Time: Capture long-term usage patterns.

- Collect feedback and artefacts anchored in the environment / real usage. This helps retrieve data about the context of usage (for example, someone using the interface in a crane on a construction site, reporting it’s hard to use in bright sun). Since it’s self reported data, it also helps with observation bias.

- Collect data that is impossible / difficult to plan or replicate. For example, in the case of my study, different tasks users can’t plan.

- Collect data in environments where observation could be complicated / impossible (for example in a prison)

Challenges

But this method also has challenges.

- It takes a lot of time for both researchers and participants.

- The quality of the data depends on how well participants log their entries.

- Self reported data comes with its own biases. For example humans are not good at analysing their own feelings. To mitigate this: keep it factual, task oriented, don’t ask people hypothetical questions (future prediction, etc.)

- Because it’s self reported, you might miss the chance to observe unexpected behaviors directly.

Despite these challenges, diary studies provided invaluable insights that helped us refine our tool before launch. With proper planning, they are a powerful research method.

Thanks for reading! If you’re considering a diary study, I hope this guide helps you get started.

Video of the talk

If you prefer the video version of the talk you can go and check it on YouTube (with automated captions).